The previous blog post, about drinking a coffee on a Sunday morning, was called When I am happy. I thought of calling it What makes me happy, but then I would fall in one of the biggest pitfalls of happiness. Let me introduce why I believe there is a subtle but importance difference.

One of the great misconceptions human beings have about happiness is our implicit belief that things (objects, but also experiences) will always make you happy – satisfaction guaranteed. Sometimes they can. In the end, happiness is an ephemeral phenomenon. It comes and goes, sometimes stimulated by the things outside us, sometimes just by our own thoughts and perceptions. Yet, I think there are three reasons why it is dangerous to assume anything will make us happy: high expectations, the need for more, and the lack of a ‘satisfaction guaranteed’ clause.

High expectations

First of all, our expectations of objects are unrealistic. We think we will be happy when we have a certain object – say, a wonderful new Ferrari. We idealise the great trips we are going to make, crossing a nice hilly countryside, wind through our hair and a wonderful girl in the passenger seat. We don’t think of possible negative experiences with this car, be it a hefty traffic fine or an expensive repair. Often there is a mismatch between our idealised image of the future and reality. When reality (traffic fines, repairs) doesn’t match idealised expectations (great rides), it is easy to be disappointed.

More! More! More!

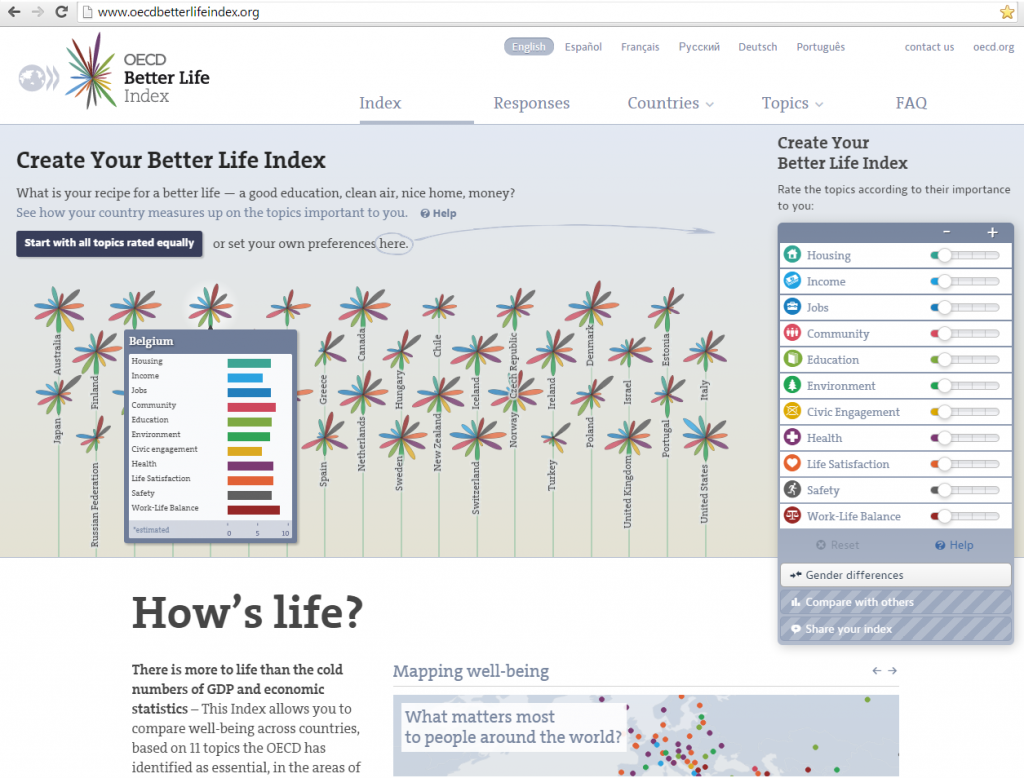

Secondly, there is one obvious mechanism. Greed. The need for more. To put it simply: when you don’t have a car, you think having a simple Kia to get you everywhere will satisfy. But then, you compare with the Volkswagen drivers. And even when you get your Ferrari, it is not enough. Then, you can’t do without a Porsche or a Maserati or a Bentley to be happy, and it starts all over. Happiness always disappears behind the horizon, like the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow that moves further away. (Personal example: my collection of ties is never complete either. I have over 35 now – and counting…).

However, I think the third mechanism is most intriguing. I’d refer to it as the lack of a ‘satisfaction guaranteed’ clause for well-being, and it goes way beyond kitchen utensils and five-step abs training programmes. Sometimes the magic doesn’t happen. Even if you have been happy before drinking great coffee, spending time with close friends or buying shoes, there is no guarantee that it will always work. In scientific terms, the stimulus is not a sufficient precondition for happiness: the relevant object or experience doesn’t always have the desired effect of making you happy. This might be the most difficult thing to accept: why doesn’t it work anymore? Why is the magic lost?

When we are happy, not what makes us happy.

What is the the takeaway of this? My belief is that it is better to see our lives in terms of moments when we are happy rather than to objects or experiences of which we think they make us happy. Happiness can come in all kind of moments, often as a surprise or unplanned. But we need to be present to register them, and to be grateful. Happy moments refer to episodes in the present, when you experience them. When we expect things to make us happy, we look at the future.

And in my own case? This particular Sunday morning I was happy drinking my coffee. But another Sunday morning, I might not be. Probably, it wasn’t only the sensation of the cup of coffee that made me happy. It was the complete picture – the excitement of trying out a new place, and the hope, later confirmed, that it would activate my creativity. It’s a lot more complex that coffee. Happiness is a messy thing.