In the three years I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve travelled around the world to explore happiness: from Denmark to Mexico and Bhutan, and from Costa Rica to the United States (well, the latter two only in spirit). But so far, I never wrote about my own home country, the Netherlands.

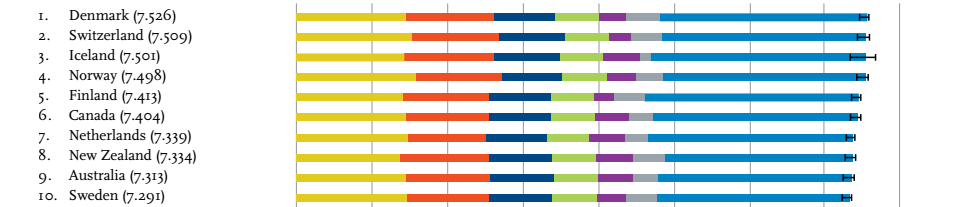

That’s not because there is no interesting debate on happiness in the Netherlands. The Netherlands always scores high in the international rankings (seventh in this year’s World Happiness Report, and fifth last year). It is home to the first Happiness Professor, Ruut Veenhoven. He was one of the first academics to seriously study happiness and his university hosts the World Database of Happiness (I’ve been told their team has identified 963 ways that have been used to measure happiness). A Unicef report often quoted in press demonstrates that Dutch children are the happiest ones of the (rich and developed) world. And beyond that, I’ve come across a lot of great projects on happiness, from happiness budgets for socially deprived people to happiness trainers and from happiness in civil community work to activists for environmentally sustainable happiness. The Dutch appear to be a happy few!

Happy people, happy state?

But does all this manifested interest mean in academia and society mean that also the national government is interested in understanding and enhancing the happiness level of its population? That is not the case. Prime Minister Mark Rutte famously stated that:

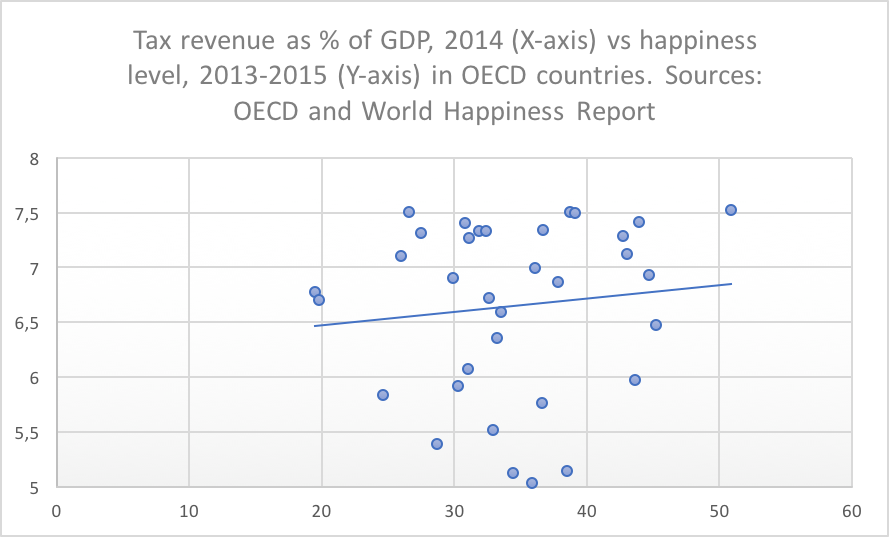

The State is not a happiness machine

What does Rutte mean by this? From the 1960s to the 1980s or even longer, many in the Dutch political elite believed in the idea of socially engineered society, or in Dutch, the ‘maakbare samenleving’ (‘society that can be made’). This idea presupposed that government intervention could achieve a lot to improve people’s lives, the quality of society, and happiness levels. Over time, in the Netherlands like elsewhere the mood has shifted to a society where people are responsible for their own lives and the state does not interfere with people’s personal sphere. Happiness, or quality of life, is seen as a purely personal issue.

In my view, that is too simplistic. In the Netherlands like in Denmark, it just appears that we are getting many factors right. Neither Denmark nor the Netherlands has comprehensive happiness policies, but in both countries the quality of education, healthcare, social security, and trust are amongst the highest of the world. That is something to cherish, but rather than an endpoint, it should be something to build on.

Happiness through reports (or biscuits!)

Instead of developing a vision and a framework on quality of life – such as in Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness, but also in the UK’s government’s programme to measure well-being, the Netherlands has resorted to another strategy: happiness by reports!

It isn’t the only one to do so. The French Sarkozy government commissioned the appraised but never implemented 292-page report on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. The German Parliament outdid the French Committee: it published its own report of no less than 844 (!) pages on Growth, Wellbeing and Quality of Life).

Dutch ‘stroopwafels’ biscuits, a way to happiness? I’d probably subscribe to that view. Source: image found on Pinterest

The Dutch Committee ‘Broad Concept of Progress’

The Dutch response came this year. In April, a Parliament Committee published its own report ‘Broad Concept of Progress‘ (Breed Welvaartsbegrip), which it managed to keep just below 100 pages. The Committee set out in an exercise with three aims: to determine what GDP measures and doesn’t measure, whether there is value in broader concepts of progress, and to propose what these concepts should look like.

The Committee does see value in using broader concepts, and evaluates international efforts, like the OECD’s Better Life Index, the EU’s Beyond GDP agenda, or statisticians’ guidance aiming to measure subjective well-being in a more harmonised way. At the same time, it acknowledges the efforts are still very divergent. The report also points the work in the Netherlands itself via the Monitor Sustainable Netherlands (Monitor Duurzaam Nederland) prepared by the Dutch Statistical Office and three advisory bodies.

Monitor wellbeing broadly

Ultimately, the Committee does not make a clear choice in answering the question how progress should be measures. Instead, it comes with three recommendations. Firstly, to broaden the Monitor Sustainable Netherlands to turn it inot a Monitor Broad Wellbeing, and provide annual updates of the level of general wellbeing in the Netherlands. Secondly, these annual reports shouldn’t end up in a drawer or the fireplace, but be debated with the government in a parliamentary debate. And finally, the Dutch government is called to contribute to the convergence of all various international efforts in wellbeing indicators.

The report doesn’t contain a great ambitious vision, but aims to set a pragmatic and practical agenda. In a debate with MPs today, the Committee seemed to have support for this approach. Hopefully, the Netherlands is making a good choice today. There’s merit in not entering too deeply into the ideological discussions on metrics, as these often arise in arguments of the kind of ‘my index is better than yours’. Instead, by putting the issue on the agenda annually and contributing to find an end in the international labyrinths, the Netherlands may slowly edge closer to develop a vision on happiness.

A trip of one thousands miles to happiness starts with the first step. Even if the Dutch state won’t be a happiness machine anytime soon, it has started a journey.