There is no plan B, because there is no planet B (Ban Ki-Moon)

Yesterday I offered some comments on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), saying that even the UN can learn something from inspiring quotes on the internet. Sometimes they are right: a goal without a plan is just a wish. Today I want to close the story, looking at Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon’s vision. And I’ll propose some alternative goals, based on happiness. What else did you expect?

Can Ban Ki-Moon help us?

Does the UN have a plan to achieve the goals? Some weeks ago I had the chance to listen to a speech by UN Secretary-General Ban-Ki Moon in Brussels and find an answer for myself. The speech and the conference were dedicated to the contribution that young people can make in development and in the SDGs.

Ban is about as boring as a diplomat can get, but struck a cool tone at the conference. He invited the audience to take selfies and spoke very upbeat about the power of people, especially young people, to drive change. He urged youth to speak up in face of injustice, to make their voice heard, and make opinions clear at the voting booth and the supermarket counter.

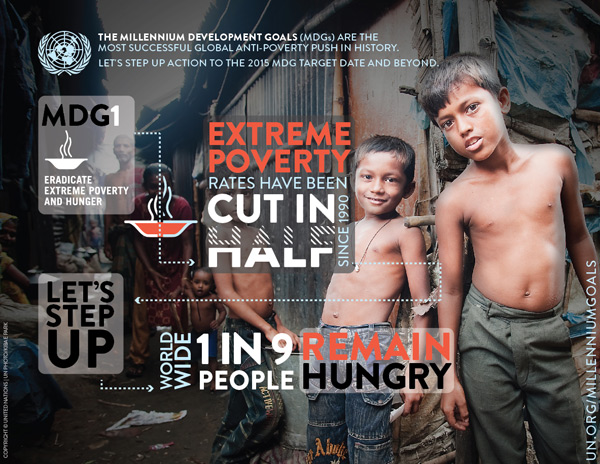

He answered a question about the failure of achieving sanitation goals with a personal story about growing up without a proper toilet in South Korea. In the MDGs, enormous progress is being made on improving access to drinking water and sanitation. Still, 2.5 billion people don’t have access to improved sanitation facilities.

On climate change, he also had a good sound-bite to show his confidence that humans will do the right thing: “There is no plan B, because there is no planet B”. As a sound-bite it is great, but one has to hope it’s backed up by concrete action.

Are we really doing the right thing?

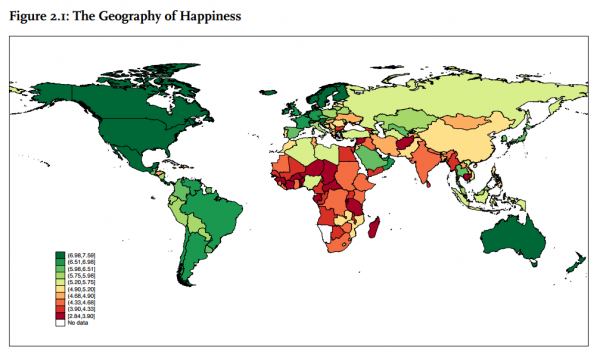

I wonder whether it is possible to find a better way to set goals and make our plans. Psychology and happiness research may offer some alternatives. The World Happiness Report finds that 75% of the differences in happiness levels between countries is explained by six factors. What if we would use these to shape our policies by six concrete goals instead?:

- GDP per capita: reduction of absolute poverty and hunger. How? Set targets for the number of people who live from less than a dollar per day.

- Social support: develop and nurture support mechanisms in families, wider social groups, and via social security. How? Set targets for the scope of social security and other mechanism.

- Healthy life expectancy: continue investment in improved healthcare, water and sanitation. How? Set new targets for infant mortality, and maternal health, and access to water to sanitation.

- Freedom to make life choices: work on gender balance and education. How? Set targets for access of women to education, work and decision-making, and targets for primary, secondary and tertiary education rates.

- Generosity: cultivate generosity via volunteerism and civic life. How? Set targets for volunteering and democratic and social participation.

- Perception of corruption (operationalisation of trust): develop a community where people trust each other. How? I’ll be honest: that’s too big of a question for me to answer.

Maybe by using happiness-based goals, we really can take a step in the good direction. Let me end with another quote, from World Happiness Report co-author Jeffrey Sachs:

“The aspiration of society is the flourishing of its members. [The World Happiness] Report gives evidence on how to achieve societal well-being. It’s not by money alone, but also by fairness, honesty, trust, and good health. [It] … will be useful to all countries as they pursue the new Sustainable Development Goals.”