Tomorrow my home country, the Netherlands, goes to the polls. The Dutch political system has a low barrier to enter the parliament. Especially this year, this leads to a proliferation of parties: there are 28 parties on the ballot, of which around 11 to 15 stand a stance to win seats according to recent polls.

The broad offer of political ideas also resulted in a large amount of online voting tools. Nowadays, about fifty sites offer tools to compare your views with party manifestoes. Apart from two big and generic ones, others help you to determine which party to vote if you are an entrepreneur, a young voter, if you want to see swift work on climate change, and even if you smoke cannabis (this remains the Netherlands…!).

A voting tool for happiness

But there is no tool on happiness. If I want to support a politician that promotes policies improving happiness and well-being, who should I vote? Does any politician ‘run on happiness’?

Happiness is a very tricky issue for politicians. Few politicians would directly promise to make their voters happy, and for good reasons. But if you dig a bit into some of the electoral manifestoes, a couple of ideas linked to wellbeing and the beyond GDP agenda do appear.

Four out of the seven large parties have some notion of happiness

Let’s run through the seven parties performing best in the polls; known as VVD, PVV, CDA, D66, GroenLinks, SP and PvdA in their Dutch acronyms.

Three of the main parties do not dedicate a single word to these ideas. For the one-page manifesto of the Freedom Party (PVV, Geert Wilders), this is not a surprise. It’s main aim is to ban things that does not make its leader happy: islamic, asylum seekers, the koran, and public expenditure on culture, wind mills, public broadcasters, etc.

For the Christian Democrats (CDA) and especially Labour (PvdA), I am a bit surprised not see a reference. Both have paragraphs on sustainable economic development, and the link to welfare and wellbeing could be easily made there.

The idea of basic income – arguably also a revision to the thinking about wellbeing – appears in some manifestoes. Some smaller parties wholeheartedly support it (including a dedicated basic income party), while Labour, Greens and Social Liberals (D66) favour experiments with this tool.

Liberals: we are happy already, nothing to do here

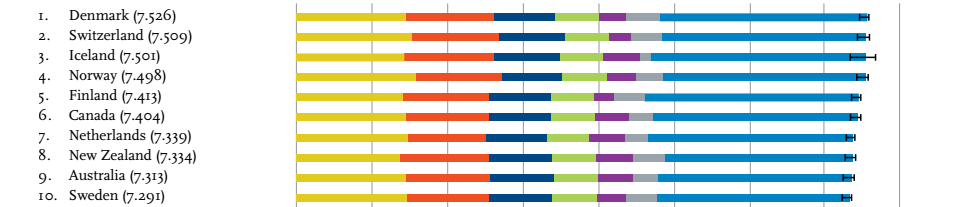

The Liberals (VVD) programme follows Prime Minister Rutte’s relentless optimism: if the Netherlands wouldn’t exist, we would invent it. We’re one of the happiest countries of the world. Almost nowhere else life is as good as here (the Netherlands second?). But the measures it then proposes do not concern happiness or wellbeing – the programme simply focuses on prosperity. Is our happiness then just a coincidence? If our basis is so strong, isn’t there any way to strengthen wellbeing even further?

Socialists: equality makes everybody happy

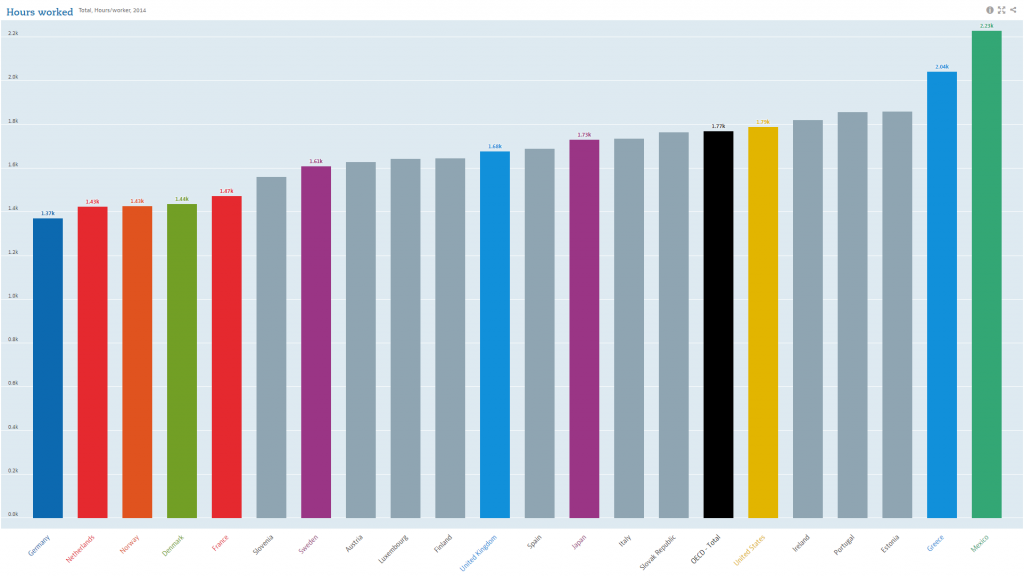

The Socialists (SP) start from the correct notion that people are happier in a country with smaller differences between people, and equality is a key objective of their policies. Elsewhere, the programme notes that there is more than GDP, and wellbeing and sustainability should be considered to measure prosperity. Surprisingly, this point does not lead to a plea for alternative indicators. Instead, the relevant paragraph continues to speak out against European budget rules…

Greens: GDP is not holy

The Greens include a section on a pleasant life, with mostly has to do with nature and spatial planning. Quality of life in our neighbourhoods should be improved, and with an allusion to Robert F. Kennedy, the programme states that “the value of the beauty of the landscape, nature and animal welfare cannot be expressed in money”.

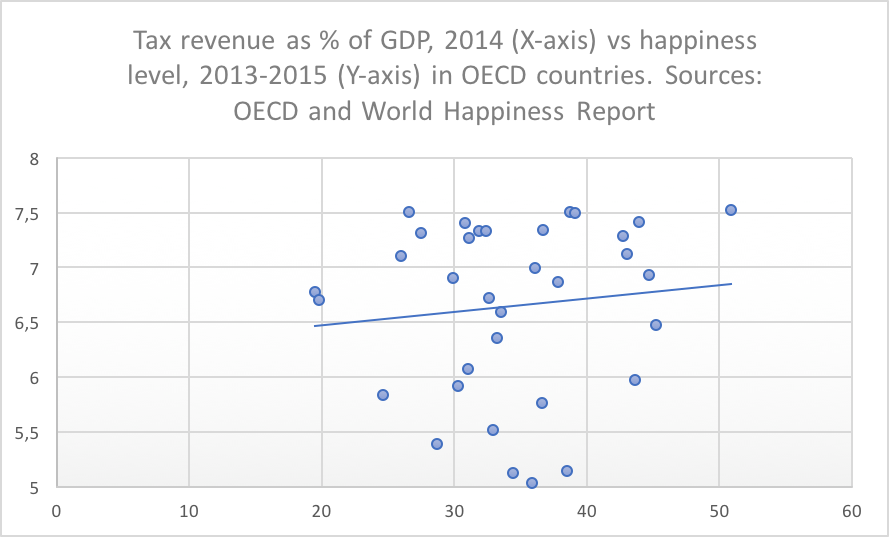

Elsewhere, the manifesto states that ‘GDP is not holy’, and that “wellbeing is a lot broader: green growth with sustainable boundaries, based on knowledge and innovation; inclusive growth, that creates good jobs and fair incomes. That is what counts.” A couple of nice quotations, surely, and the manifesto is full of utopian ideas to get to such a society. Indeed, according to the Central Planning Agency that reviewed the impact of most parties’ programmes, the Greens gets us very far in reducing income differences. Revision in the taxation system should finance this: the Greens are the most radical in greening the taxation system via the ‘the polluter pays’ principle.

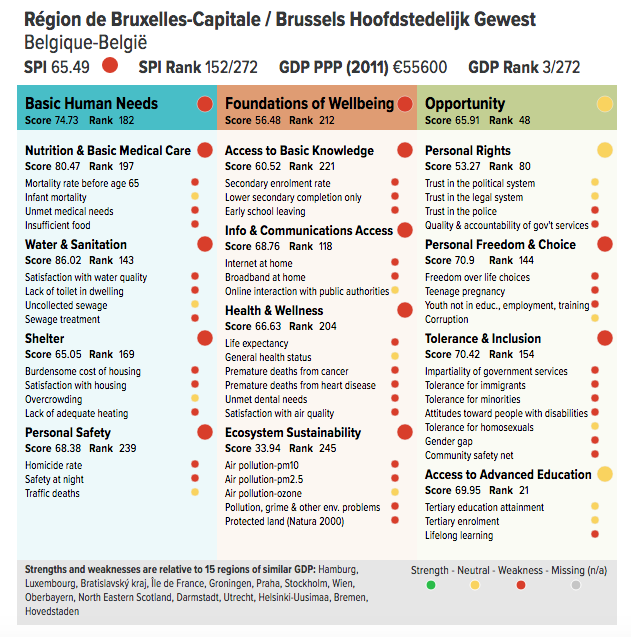

Social Liberals: measure wellbeing

The Social Liberals (D66) denounce both the dogma of a government that steps too far back and the dogma of the state as a ‘happiness machine’. The programme notes that employment and social expression contribute to people’s happiness. The party also has the most detailed view on measuring wellbeing. In a dedicated paragraph, the party states that we should not only measure GDP, but also evaluate our ecological footprint, welfare, and wellbeing. These elements should be evaluated to determine our success. And based on an amendment proposed by your happiness blogger, the programme also links this to the efforts ongoing on the Netherlands to develop an alternative indicator in the form of a ‘Broad Wellbeing Monitor’.