When we meet new people, why do we always ask them where they work? Why is the place where we work so defining for our identity? And is it morally permissible to be happily unemployed?

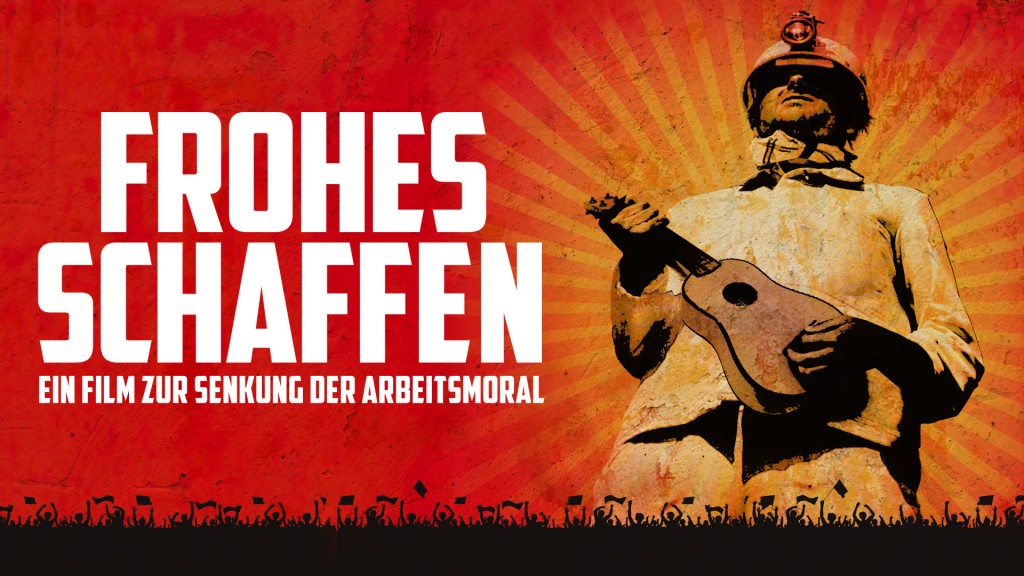

These are some of the questions that Konstantin Faigle researched in his film ‘Keep Up the Good Work’. The German original version is released under the more apt title ‘Frohes Schaffen. Ein Film zur Senkung der Arbeitsmoral’.

I very much recommend you to see the film. Faigle’s film is a combination of two elements: a documentary about work and a series of personal stories on what work means to his characters.

The craze of work

Let’s start with the documentary. The ‘talking heads’ all underline how crazy our relationship with work has become. From the Industrial Revolution onwards, productivity has risen, and work has become so much more than subsistence. Most of us spend more time at work than we know that is good for us. Have you ever met someone who regretted leaving work early? With smartphones and teleworking, work is more invasive of our free time than ever before. Let me give two examples how serious this is: people who are close to retirement can now get a ‘pensioner’s coach’ or see a psychologist to redefine their purpose and find a way to fill their seas of time. And the Japanese language has the word ‘karoshi’: death by overwork.

According to meme expert Susan Blackmore, work has become a ‘memeplex‘: a powerful social construct, grouping various ideas and concepts that define what work means to us. Work becomes an essential part of our lives and our society. In the movie, German philosopher Michael Schmidt-Salomon even argues that work has become our new religion. In the current system, factories and offices replace the church as the place where we profess our faith.

15 hour working week

It’s absurd that we are spending so much time at work. In the 1930s, Keynes though that in two generations, people would only need to work 15 hours a week. If we were to do so – by distributing work evenly across the population or use increasing productivity to work less and keep output constant rather than to increase our economy, we’d probably have to take some lessons from Tim Hodgkinson, the Founder of the Idler’s Academy on Philosophy, Husbandry and Merriment. Though the clip is not available, the picture below gives an impression of one of the brilliant part of the Idler’s Academy lecture series: staring at the sky. (This clip, on idle parenting, also gives an idea of his style).

Happily unemployed

Faigle also addresses the question whether it is possible, and morally admissible, to be happily unemployed. In countries with protestant working ethics, like Germany and Netherlands, this is an inconceivable concept. In one of the funnier scenes of the movie, Faigle hits the streets on Labour Day with a Jesus-like figure stating that Jesus was happily unemployed. People seemed to be more upset about the idealisation of idleness than by the portrayal of a religious figure!

Faigle’s movie features some characters that for various reasons (dismissal, freelancer without any assignments, retiree, etc) do not work and thus suffer from a lack of purpose in society. But when they meet of one of Faigle’s more cheerful characters, a ukulele-playing guy working as a part-time mattress salesman, they miraculously start to appreciate life.

It is a nice story, but a bit simplistic. Faigle is right in denouncing our working craze. Having A Career is imperative; work is not just something that provides the income and security to live our life. But Faigle neglects that work also gives us a purpose. Part of our identity is defined by the difference we make every day for our clients, customers, patients, students and colleagues. The labour market in the West has progressed. There is a fair amount of dull jobs, but many jobs do carry meaning and bring about a state of flow. Work can also be a source of happiness. And when it’s too much, just play your ukulele for a bit and you’ll be fine.