For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!

In his essay on “The Economic Possibilities of Our Grandchildren” from 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes famously predicted that in the future, people would only work fifteen hours a week. In hundred years, he wrote, the standard of life in progressive countries would be four to eight times higher than in 1930. In the extract above, he wrote that for ‘the old Adam’ in 1930, a fifteen-hour working week would be necessary to fairly divide the available work across the population.

With 14 years to go, there’s still a lot that needs to be changed!

Considering the gap between current working hours of 35 (officially in France), 40 hours for most and 50-60 or more for workaholics, maybe we should strive to reduce our working hours in smaller steps at first?

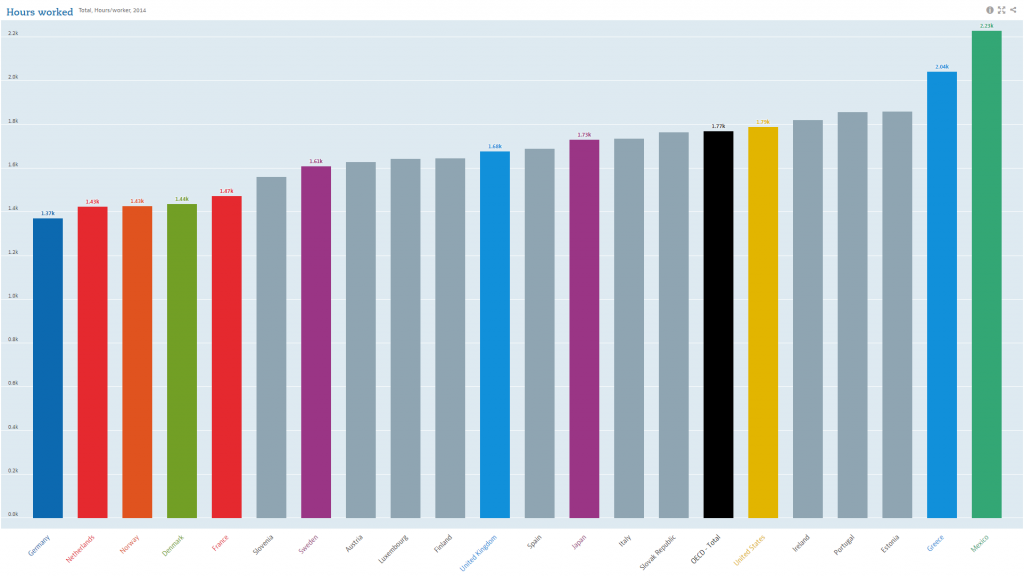

According to OECD data, the average working hours per year stands at 1770 hours per year across the OECD countries. These are not equally divided through the year (think of Easter, summer, and Christmas breaks): the weekly average is probably around 37 hours. These figures are actually worked hours, per worker, so including part-time workers and seasonal labour.

Against prejudices, the number of hours stands at 42 in Greece; in Germany and the Netherlands, the average is around 30. In the latter two, these figures are skewed by the high proportion of part-time workers, but also can be seen as a sign of high labour productivity! And surprisingly, it’s not Americans or Japanese that put in most hours. Instead, the workaholics of the OECD live in… Mexico. At 2238 hours per year and some 45 per year, the average person’s working week is some 50% longer than in Germany and the Netherlands.

Step 1: down to 30 by 2020

What if we could achieve this level of 30 hours without these tricks? In their history, the Green and Socialist Parties in Sweden have aimed to reduce working hours to 30 per week. Scandinavian countries have a reputation for a healthy work-life balance and indeed are towards the left of the curve. Swedes work a bit more than the French with their 35-hour working week policy.

Last year, a retirement home in Gothenburg started to experiment with a 30-hour working week. Nurses tell researchers they feel they have more energy. The experiment is funded with a subsidy of around 500,000 euros to compensate for the higher number of staff needed to care for the residents.

But other examples cited in another article, such as creative and service industries, suggest that not so much more staff is needed. People still want to do a good job, and may achieve similar levels of productivity in six hours as in eight, says an app developer. With some testing and refinement, wouldn’t we able to get this rolled out by 2020?

Step 2: let’s get down to 21 by 2025

From the perspective of the new economics foundation, a think-tank on “economics as if people and the planet mattered”, getting down to 30 is good, but only halfway there. In a pamphlet and a TEDx talk, researcher Anna Coote argued for a 21-hour working week ambition (she herself, a recovering workaholic, is at 30 hours).

She argues that shorter working weeks would have a range of social and environmental advantages. For instance, it would distribute work more evenly across society, and hence reduce unemployment, and increase our ecological footprint. Now, we are getting close to Keynes’ expectations 85 years back. Doesn’t it sound utopian to work only four/five hours per day, four or five days per week? Or is it really feasible to do this within ten years, coinciding with decarbonisation of the economy and lower energy use to meet the targets of the COP21 climate change agreement?

Step 3: down to 15 by 2030 – or why not limit us to 4 hours?

But for the American dream, 21 hours is not good enough, and we might be able to do better than Keynes’ 15 hours. American dream salesman and self-help author Tim Ferriss wrote a well-known book entitled the ‘Four-Hour Working Week‘. In the book, he explains that for most entrepreneurs, a small amount of clients brings in most of the revenue. As such, by focusing on these, outsourcing all support functions, and living in low-cost countries, Ferriss claims it is possible to only work four hours a week. Whether you take this as a serious career option or too-good-to-be-true, it’s not a model that could apply to society as a whole.

If everybody were to work only four hours, our economic system would come to a stop. But Keynes 15 hours? If we really change our economy’s paradigm, maybe we can get it done by 2030…