A life without purpose is no life all.

Our purpose – a key element of a happy and fulfilling life – could be radically overturned by the rise of robots. Automation and artificial intelligence, sometimes referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, are threatening work and the economy as we know it. With that, even our happiness levels could be at risk.

The robots are coming

A seminal study on the future of employment by Frey and Osborne of 2013 put the figure of US jobs that could be automated by the early 2030s at around 47%. Imagining that about 1 in 2 employees lose their jobs is massive, but it is an average. For some sectors, like truck drivers or cab drivers, the figures are 70% or higher. If self-driving cars deliver on their promise, they will drastically reduce, or even eliminate, deathly car accidents. They will also radically cut employment in a sector that now represents about 3% of the US economy, and offers people with low education access to a middle-class lifestyle.

The gastronomy sector is another example. In a few years, you can order your pizza capricciosa online, and have it delivered home without any human intervention (we’re already almost there, though we still need a few humans). The dough could be prepared by one robot, the stuffing and sauces by a second, a third could bake it, and it could be delivered to your doorstep by driverless vehicle. Hygiene and efficiency would increase. For a capitalist, it is great: robots can work 24/7, without asking a salary, requesting additional training, getting bored, or going on strike.

White collar jobs are also at risk

But it’s not only blue collar jobs that can lose out. Also part of complicated jobs, like lawyers, accountants or radiologists can be automated. Again, their performance can be better than of humans. A well-programmed (or ‘trained’, through machine learning), robot accountant does not make the mistakes a human makes. A robot radiologist sees more cases during its training that a human during their entire career, and scores better in its diagnoses. These are just some examples: robots might also threaten your job, because humans can be beaten in every repetitive task.

Dramatic social effects

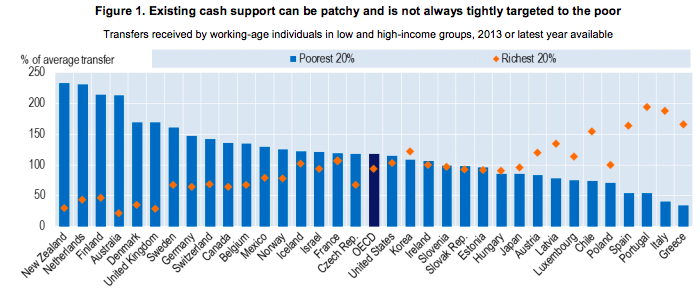

All these developments have massive social and economic effects. If robots take over so much of the current work, what will we do? Can we create new jobs for the 47%? Or will only be half the population be able to be employed? The demand-and-supply laws would posit that salaries would go down. Only those who control robots, the new means of production, would earn good salaries. Inequality would massively increase. This development is already visible in places like San Francisco. A four-person family with an income below $105,00o is now considered poor.

Maybe the entire economy would collapse. If only few people work and earn salaries, who can afford to consume of all products and services that robots produce? Henry Ford’s production line only started to take off when he realised that he needed to pay his staff enough to buy his T-Fords. Supply is nowhere without demand.

A new social contract?

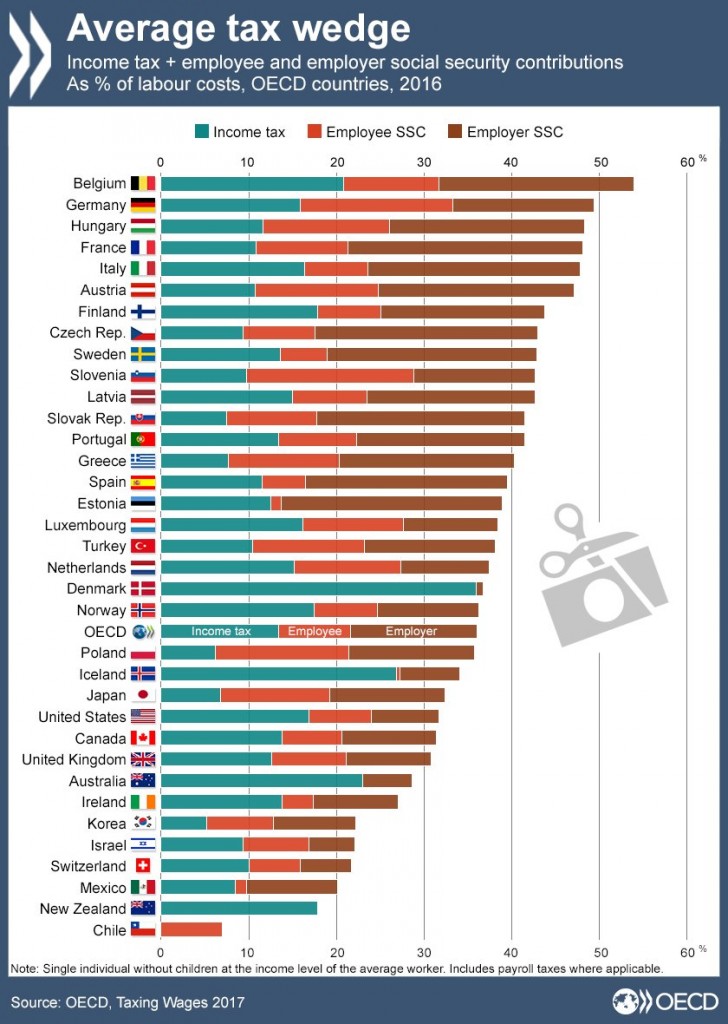

Many in the tech industry, from Elon Musk to Mark Zuckerberg spoke out on basic income as a tool to protect those who lose out. In an interview last year, Bill Gates advocated a robot tax: “The human worker who does, say, $50,000 worth of work in a factory has his income taxed and you get income tax, social security tax, all those things. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think that we’d tax the robot at a similar level”. Policy makers, such as San Francisco counsellor Jane Kim, have started to think what it could look like. Basic income might be part of the new social contract in a robot-driven economy – who knows?

What is our purpose?

At the moment, we have many more questions than answers. We know robots can do many parts of our jobs, and that some sectors are destined for radical transformation. But we don’t know what comes next. When coal mines in Western countries were closed in the 1970s and 1980s, nobody could tell coal miners not to worry – we didn’t know yet that their children and grand-children could make a living as social media managers or YouTubers.

Similarly, the jobs that will be needed in the 2030s may not exist yet. At the same time, there are a few things that can give us hope. Coding is safe – robots cannot programme themselves (yet?). Social skills and social relations will remain important. And while robots are great in performing repetitive actions in situations they have seen before, they cannot (yet?) deal with completely new situations and decide what to do.

So, there are at least two avenues to find our purpose: one is to do the non-routine, creative work that is hard to automate (some creativity can be automated though – robots can create music and paintings). Another thing we can imagine is living the life as in Keynes vision – with a 15 hour working week, we can spend so much more time on holidays. There are a few big ifs – firstly, we need to have a new social contracts that allows it. Secondly, we need to find a raison d’etre, a purpose outside work.

We should hurry to do so. The 2030s are close.