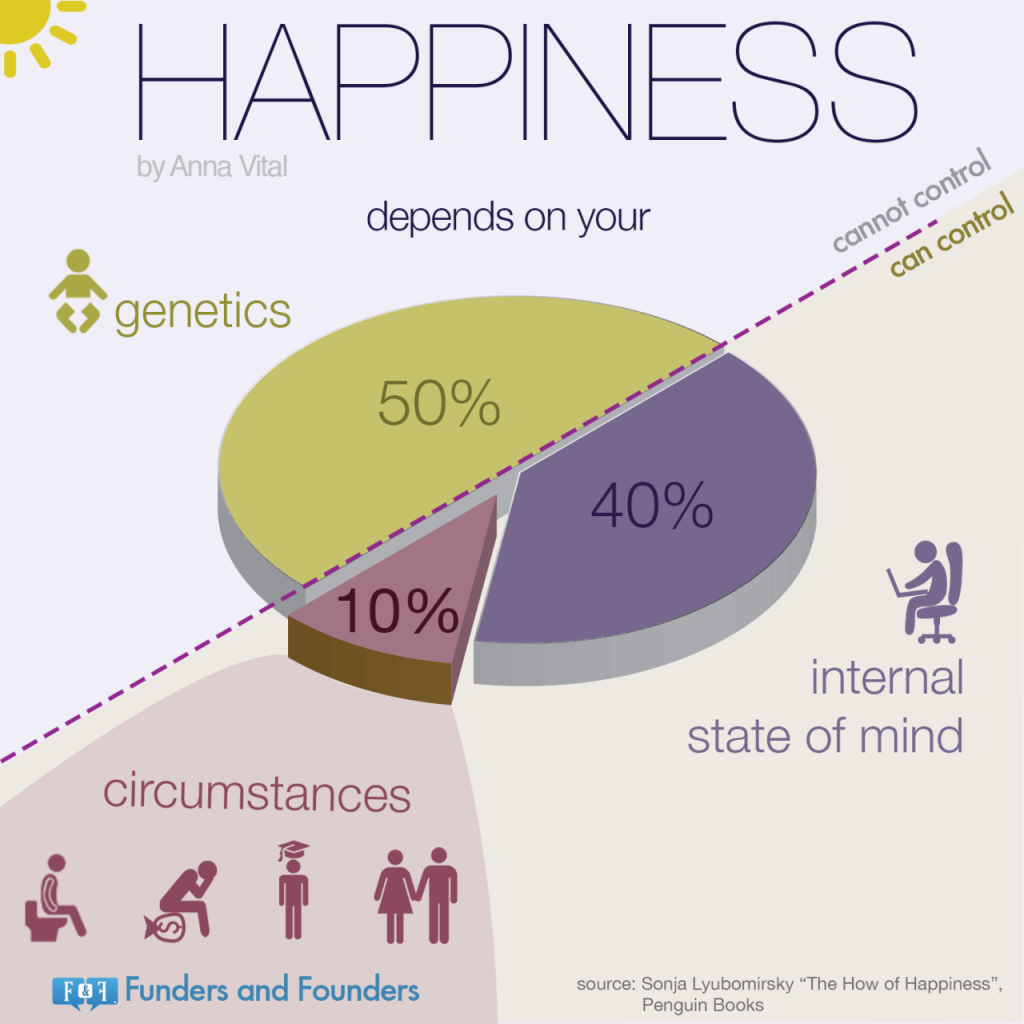

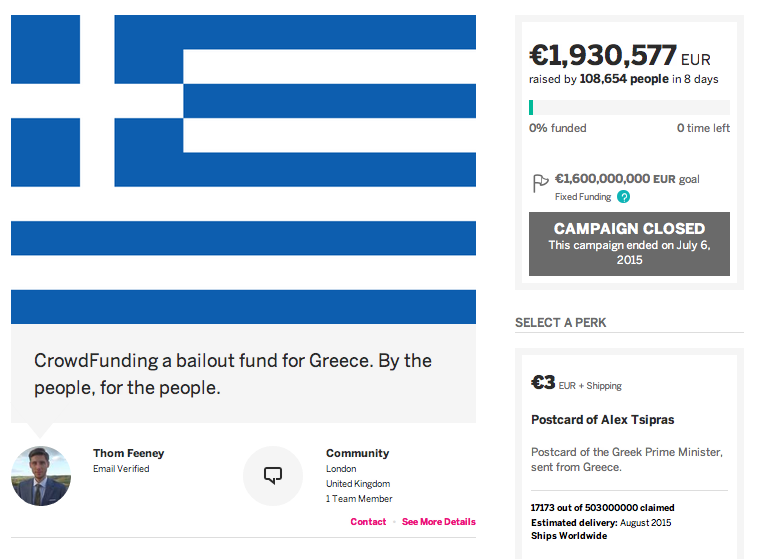

One of the most quoted facts about happiness goes as follows:

50% of happiness is determined by your genes.

10% of happiness is determined by the circumstances in which you live.

40% of happiness is determined by your actions, your attitude or optimism, and the way you handle situations.

These figures are often quoted by positive psychologists to back up claims that at least a part of our happiness is man-made. It’s a comforting message: despite the fact that there is a certain genetic disposition to be happy, there are many things in life that we can change to be happy. 40% is a large margin of manoeuvre! Imagine that we could control 40% of the weather, or the traffic on the our way to work.

According to these theories, happiness would look like this:

Source: Funders and Founders, based on material in ‘The How of Happiness’

The famous 50-10-40% formula is prominent in work done by positive psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky. Based on a body of research in this field, she and her colleagues argued that approximately 50% of variance in happiness is determined by genes, and 10% of variance in happiness is determined by circumstances. Automatically, that would leave 40% that we can influence.

Except that, there is a lot that’s wrong with the figures and the interpretation.

Variance in happiness does not equal happiness

To start with the first important nuance: these figures explain the variance in happiness – or the variation in happiness between different people. That is, genetic factors – or the presence of heritable personal traits – can explain about 50% of the difference in happiness levels between two people. It’s a small, but important detail. It means that if one person scores a 7 out of 10, and another person scores an 8, 50% of that 1-point difference could be due to genetic traits. That is not the same as saying that for a person that scores an 8, half of its level of happiness, or 4 points, are due to genetics.

Why 50% genetic, and not 40% or 60%?

Where does this theory come from? A 1996 study by Lykken and Tellegen compared well-being levels of samples of pairs of identical and non-identical twins in Minnesota, either raised together or apart. This differentiation allows to test both the impact of same or different genetics (identical vs non-identical) vs same or different environment (raised together or apart), e.g. both nature and nurture effects. Namely, identical twins share the same genes, and non-identical ones do not.

Lykken and Telleken found that the correlation of levels of well-being of identical twins in both cases are around 50%, significantly higher than for non-identical ones (2-8%). As such, they conclude that around half the variation is determined by genetics. This would leave another half determined by other factors. But it is important to note that this particular study has a limited sample. The smallest groups consists of only 36 pairs or 72 people. From a sample of twins in Minnesota, it is hard to draw so strong conclusions for human population as such.

Is it so simple?

The variance in happiness is not the full answer. In a comment of the preference of positive psychologists to favour well-rounded figures, Todd Kashdan notes a couple of other issues with genetics.

The first points is that personal traits – influenced by genetics – are not stable over life. Traits are shaped by a process called ’emergenesis’. When a characteristic is ’emergenic’, it is affected by the interaction of a couple of genes together. This might result in a behavioural predisposition to be extravert, self-controlled, or any other trait. (And similarly, there is not one ‘happiness gene’).

So far so good. But the way these genes work out is affected by many other factors. One example Kashdan mentions is that toxins or nutriments in a person’s environment can switch genes ‘on’ and ‘off’. In turn, the functioning of an individual gene can affect such an emergenic factor. If you add or take away a block from a tower, it will look different.

This reminds me of another example I learned about at a course on happiness. A certain individual may have a genetic predisposition for leadership. But if he grows up in an environment where resulting actions are suppressed, the talent will not come to fruition. As such, genes could be seen as ‘enabling’ factors, that only result in an outcome (such as happiness) when underlying conditions are met.

Genes interact with the environment

Another important issue notes is the interaction of genes and environment. In the same article, Kashdan writes that

Much of what influences our personality has to do with the presence of (positive and negative) life events and our response to choice points. Do I approach or avoid my co-worker who regularly demeans me? Do I wake up early and workout or sleep in? Do I ask out the girl I’ve had a crush on for months or do I keep my feelings to myself? No single decision matters but the patterns do. The decisions we make, the people we surround ourselves with, and the behaviors we engage in, are the building blocks for the quality of our lives. Small changes accumulate over time leading to large changes in who we become.

Our personality is the result of a complex process, in which genes and environment interact. Can we really put a hard number on that?

Happiness is not a formula

My answer is no. There is no comfortable formula for happiness. What we can say, is that our genes play an important role in determining happiness. But so do other factors, including our circumstances, environment, and our actions. Happiness is not a hard science. It is a way too complex phenomenon to quantify. But maybe that’s one of the reasons why it is so fascinating.

Rather than like a pie chart with three elements, happiness may rather look like a complex system:

The Internet as a Complex System. Source: opto.org