“Not everything that counts, can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

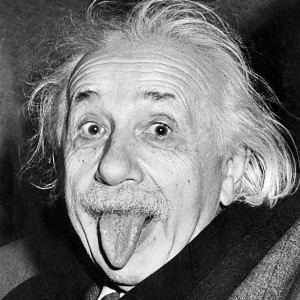

Attributed to Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a brilliant man. He revolutionised science with the theory of relativity. He was the subject of some wicked photographs – we’ve all seen the iconic photos of the great scientist with his tongue outside his mouth and with his electrified hair. And, if we believe what we are being told, he has authored a collection of aphorisms that rivals Oscar Wilde’s and would most certainly be an instant bestseller.

Reportedly, his timeless jewels includes quotes like

“Put your hand on a hot stove for a minute, and it seems like an hour. Sit with a pretty girl for an hour, and it seems like a minute. That’s relativity!”

and

“It’s better to be an optimist and be wrong, rather than be a pessimist and be right”

Did he really say that?

Wonderful quotes, but did he really say that? The classic internet joke attributes the statement “The trouble with quotes on the Internet is that it’s difficult to determine whether or not they are genuine” to Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, the internet has brought misattribution to the next level.

The quote about counting, an almost mandatory reference entry in any article about Gross Domestic Product and well-being – is not the fruit of Einstein’s ingenious brain. Quote Investigator writes that instead it has been authored by sociologist William Bruce Cameron.

The second one is autenthique, and given its subject is relativity, that is not surprising. The authorities of Wikiquote contend that Einstein suggested his secretary to use the comparison with hot stoves and pretty girls as a way to explain relativity to the general public.

The source of the third quote on optimism is unclear and it is attributed to various famous people. As a generic quote, it must have been around for long. And anything accredited to Einstein does get more weight.

Is it a problem that Einstein can only be proven to be the author of one of these three quotes? The technique, piggy-backing on a famous name, is often used in commercials (‘recommended by Rafael Nadal’, ‘used by Emma Watson’). I wouldn’t advocate the creation of a League for the Correct Attribution of Aphorisms to right all wrongs. But from an artistic point of view, the original source deserves to be mentioned.

In the current times, individual creativity and originality are highly valued. We don’t live in the middle ages anymore, where the subject of the art counted most. Often themes were openly copied (or blatantly plagiarised, in a more modern interpretation), and mostly left unsigned. Times have changed. A quick online search when you want to use a quote is the least one could do. William Bruce Cameron deserves some credit.