As so many in Brussels I’ve been following all the news about the Greek crisis on a daily basis in the last weeks. I have followed these events professionally. I reviewed the politically progress in the talks, the economic impact on the eurozone, and contemplated the scenarios for further developments.

But with this professional distance, it is easy to forget how saddening these developments are .

Staying away of the question who is at fault, the tragedy is that politicians don’t come closer to each other. Countless meetings at ministerial level and several Euro Area Summits are ineffective.

The referendum about the latest EU reform proposals divided families between those who wanted to show their opposition to austerity and those who felt that no deal might be worse than a bad deal.

And Greek society suffers under extreme stress, as pharmacies run out of some medicines and banks don’t release more than sixty euros per day.

Pensioners – who often have the only income for a family of unemployed people – have to cue hours to receive 120 euros of their pension.

The best way to sum the crisis up may have been the picture of the crying Greek pensioner that made way of media in the last day. The photo is by Sakis Mitrolidis (AFP). The man on the photo broke down after being refused his ‘allowance’ by four banks in a row in Thessaloniki.

Effects on happiness

It should not be a surprise that a country in crisis is not a happy country. In psychology, there is a concept of ‘loss aversion’. Humans are surprisingly adapted to live in hardship. That is, if they are used to it. The impact of winning an additional hundred of euros in income is marginal compared to the negative effects of losing one hundred euros. In dollar terms, Greeks are not so miserable with a GDP per capita of $21,687 in 2014. That’s about 1,5 times Polish GDP and twice the level of Turkey or Mexico. But whilst the latte three have grown their income in the last five years, Greek GDP is about 20% lower than five years ago.

This crisis also has a marked effects on happiness levels. The 2015 World Happiness Report does not only have figures for 2012-2014, but also compares them with the period 2005-2007. Greece is the biggest loser in happiness worldwide, scoring almost 1.5 points lower now than before the crisis. On a ten points scale, Greece’s happiness now stands at 4.857, ranking 102 out of 158 countries polled.

When Greek Prime Minister Tsipras and EU leaders that do want to show solidarity, they speak about taking measures to address the humanitarian crisis. Apart from that, there is also a psychological crisis or a ‘crisis of happiness’. Well-being of Greeks is further under pressure.

What to do?

It is clear that a political solution is needed to take away some of the uncertainty and distress. I am optimistic that yesterday’s Summit, the latest in the row, is allowing some progress. There is no financial programme yet, but the message is that it can be done in the next five days.

For the crisis of happiness, what we need is positive stories coming out of Greece. Shows of solidarity and support help.

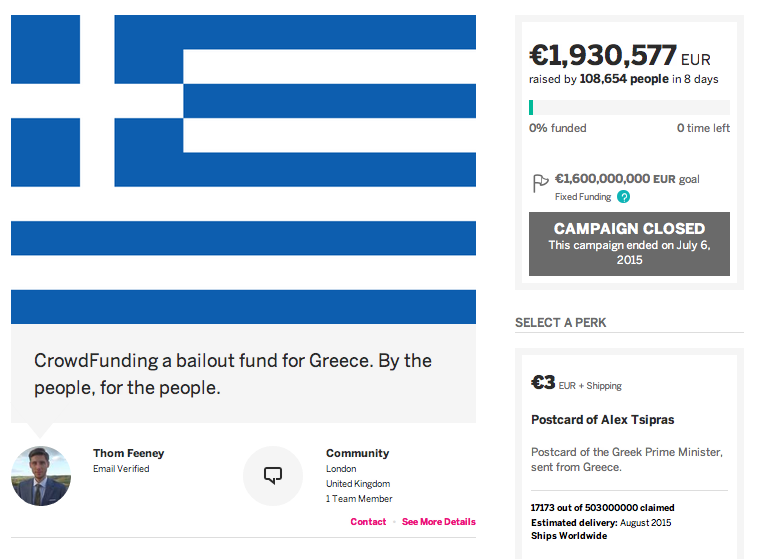

A great example in the last week is the effort of Thom Feeney. He decided that if EU leaders couldn’t agree on a bailout, he would crowdfund €1.6 bn for Greece to repay the IMF himself. Maybe not so surprisingly, the effort failed (and the money was reimbursed), but with over €1.9 mln collected in a week time, his campaign did send a more positive signal about EU populations’ support for Greece. It’s now followed by a second campaign, aiming to raise €1 mln in humanitarian aid.

Also in the case of the Greek pensioner, the severest crisis resulted in a positive response. An Australian-Greek businessman – whose father grew up in the same village – heard about the story and decided to support the man with twelve months of pensions money.

These are only two stories. They reach a small number of people and can by no means solve all of the crisis. But they offer glimmers of hope that the days of gloom may be over.