Another month, another happiness book. My third read of the month was The Art of Being Unhappy (De kunst van het ongelukkig zijn), by Dirk De Wachter. After books focusing on what well-being is and on happy memories, it was time to look at happiness from another angle: is it sensible to pursue happiness, or should we strive for something else? And when we inevitably do face moments of unhappiness, how can we deal with them?

De Wachter is a psychiatrist. His perspective on happiness is different than most of the people I usually read, many of them positive psychologists. As a psychiatrist, De Wachter sees human sadness and depression in his practice every day. His diagnosis is that the idea picture of individual happiness leads many people to selfishness; or where they fail, to loneliness.

Finding inspiration in philosophy and poetry, De Wachter criticisises how people need bigger and bigger successes to experience happiness. We shouldn’t be contend to cycle up the Mont Ventoux; no, we ride up from the most complex side, twice. Running a marathon is not enough, we need to run three. To be special as individuals, we need to have ever more special experiences. And of course, they only matter when they are showcased on social media.

As a consequence, we are never special enough. Inevitably, unhappiness strikes. Is there any escape of the unhappiness we suffer due to our unsuccessful pursuit of happiness?

Don’t pursue happiness. Strive for meaning.

De Wachter claims that it is a mistake to have the pursuit of happiness as a major goal in life. When we strive for happiness for its own sake, it will never be enough.

Instead, we should become aware of the unhappiness in ourself and around us, and take that as a basis for social engagement: being aware of our own moments of unhappiness and the unhappiness around us can be a force for good, to motivate us to care about others or about social problems. According to De Wachter, real happiness is not found in individual experiences, but in doing meaningful things for others. That is what we live our life for. The ‘Art of Being Unhappy’ is the art of finding meaning in acting for others.

Hedonic and eudaimonic happiness

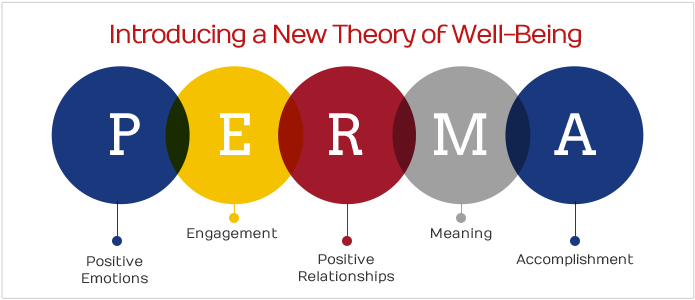

De Wachter is of course right that a life of happiness requires more than pleasure – the hedonic type of happiness. We feel more fulfillment when dedicating time to something bigger than ourselves. Often, this is understood as ‘eudaimonic’ happiness, which is based on a less fleeting and more permanent form of happiness. Feeling there is a purpose to our life is an important factor to our wellbeing. Indeed, theories of happiness and well-being – such as the PERMA model of prof. Seligman I discussed before and that we use as the foundation of our happiness vlog – see meaning as a key component of a happy life.

From all components of well-being, I feel, meaning is the most complicated one. Spending time in activities you enjoy or with people you like is easier than to find your source of meaning. But maybe the struggle to give a meaning to our lives is simply a part of life.

For many people, our purpose is in the others around to: taking care of children or family, dedicating ourself to protecting the environment or animals. Having a bigger reason to live, thus, is just as important as being able to enjoy the small pleasures of life. Thus, forget the ride up the mountain and profiling yourself online; dedicate yourself to a bigger cause instead.