A few weeks ago, I spent a few days in Varanasi, India.

It wasn’t the easiest place I have visited. I was confronted with a sweltering heat, pollution affecting my breathing, occasional smells of cow dung and rotting garbage, and a cacophonous concert of auto-riksha horns that resounded in my head long after I returned to the calm of my hotel.

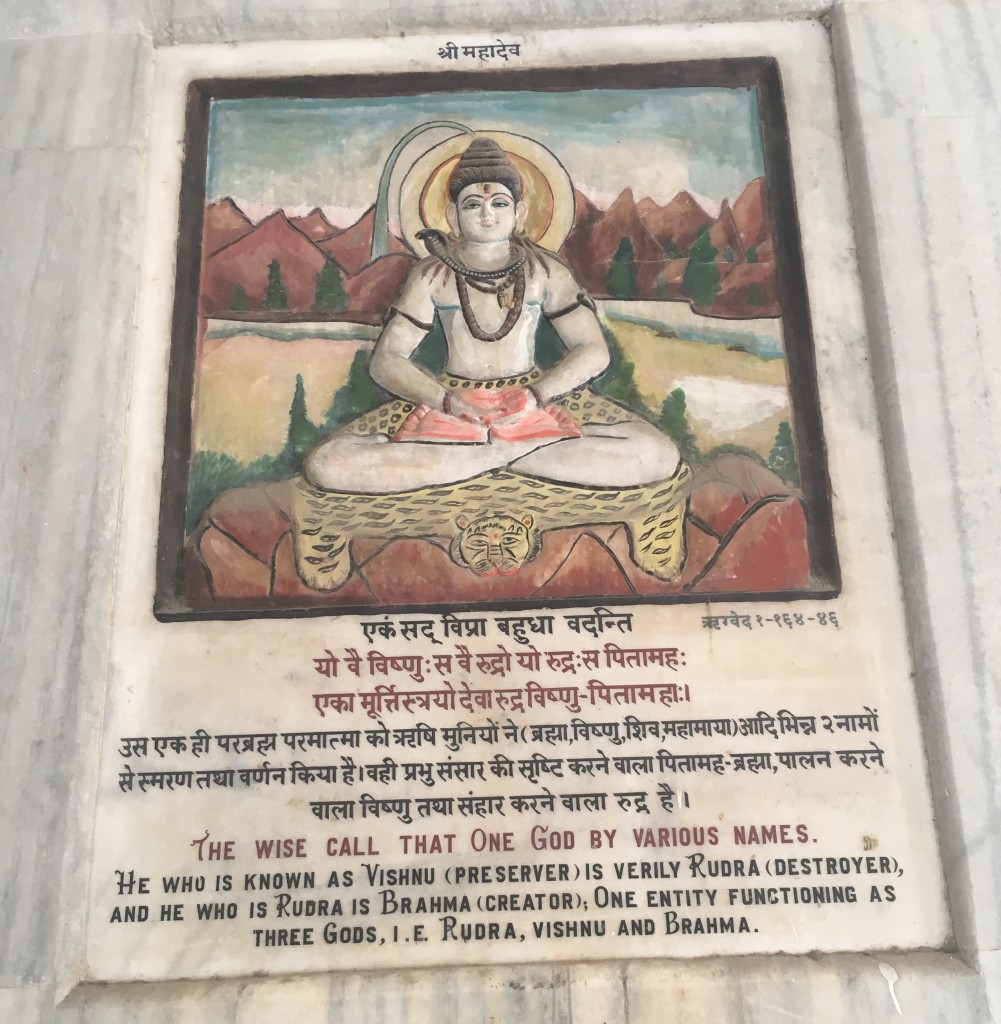

At the same time, it was the most mind-blowing of all the places I had the fortune to visit. Varanasi is so different from any other place I have visited. I enjoyed visiting the temples, and learning how Hindu Gods are portrayed. Did you know that Hindus have 330 million Gods? They are not only above us, but everywhere around us.

I was fascinated to walk past the Ganges, the holy river, and witness how pilgrims came here to bath in the river, wash their clothes, and drink a few sips of holy water. On the riverbank of the Ganges, a few sets of stairs are used for the cremation of those who are lucky enough to die in Varanasi. According to Hindu mythology, if someone dies in Varanasi, their soul escapes the cycle of death and rebirth. Hence the streets are lined by pilgrims, among them many long-bearded men dressed in orange, waiting for the moment to liberate their soul.

The unique spirituality of the place, in my opinions, far outweighs the discomfort. And it perfectly illustrates why we travel in general, and why our travels can generate such moments of happiness.

Why we travel

The question ‘why we travel’ seem simple, but is not that easy to answer. For me, travel is a complex art of relaxation and adventure. Overall, I think there are five important reasons:

– to relax: to gain new mental and physical energy, or enjoy lazy days with sea and sunshine

– to learn about the world around us: experience different ways of living in other nations (people already have been doing this since the Roman times! A geographer named Pausanias even wrote a travel guide to Greece in the 2nd century AD).

– to admire beauty: to experience the beauty of nature, art and culture

– to meet new people: to gain fresh perspectives and ideas by meeting people from different cultures or in different settings than home

– to escape our comfort zone: while we need stability, we quickly adapt to our daily reality and bored. Travel helps us to break routines (and boy, did I do so in India!)

Travel, for a 2% happier life

Travel creates many moments that could experience happiness: relaxation, learning, beauty, and social encounters. At the same time, travel can also lead to difficult and stressful situations.

Altogether, there is only a small net positive effect of travel of happiness. Compared to people who do not go on vacation, people who travel have a slightly higher level of subjective well-being. According to this PhD study on leisure travel and happiness, holiday trips account for about 2% of the variance in life satisfaction. Probably, the effects are limited due to the simple fact that a vacation ends pretty soon. A few weeks after, sweet memories disappear to the back of the mind and daily routines take over again.

Nonetheless, there’s a clear stream in research suggesting spending money on experiences – which would include travel – rather than material goods is the way to go. While the novelty of a purchase wears off, triggering memories of the holidays through souvenirs, pictures or reading journals helps to keep the experience.

I think I’ve those boxes ticked: I write this on the couch next to pillowcases with elephants bought in India and lighted up this post a few pictures. And describing my experience in Varanasi at the start of the post almost made me hear the chaos of riksha traffic and admire the sunrise from a Ganges boat again. It is as if I haven’t left India yet.