On the road to discover how happiness works, I learned a lot about happiness in my own personal life – and in your personal lives, too. I’ve also gained a lot of insight in happiness at work. But the main focus of my research effort has been around another question: is there something our governments can do to make us happy?

Allow me to dwell on this question today, before I start my ‘sabbatical’ as a blogger.

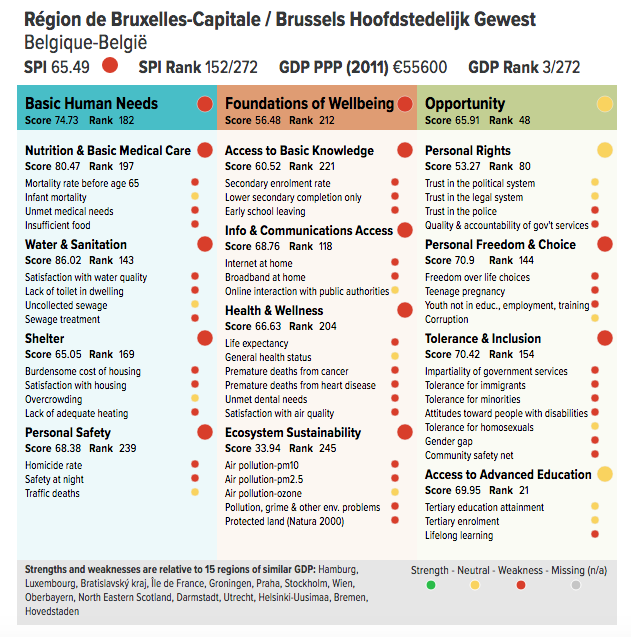

I am sure that governments can make us happier, and that they should aim to do so. There are many governments that are taking happiness-based data into account when setting policies. Gross National Happiness (GNH) in Bhutan is more of philosophical guide than a hands-on policy tool, but it shapes the narrative of the government’s action. Regions in the EU and elsewhere learn from the OECD Better Life Index and Regional Well-Being Index and from Social Progress Index (SPI). And on the local level, there is an uncountable number of projects where municipalities and social society players take happiness as inspiration in social, environmental and other projects.

GDP, an increasingly poor measure of prosperity

On one of the bigger and more abstract questions I have countered on the road is whether our data helps us to work on happiness. I’ve time and again argued that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has plenty of limitations. Instead, I assessed the virtue of alternative indicators mentioned above. And I have been far from alone in this endeavour. Back in 1968, Robert F. Kennedy already decried that GDP measures everything, except that which makes life worthwhile. In the last ten years, the debate on ‘beyond GDP’ has been particularly fierce. A cover article of the Economist some months ago summarised these limitations very well, and labelled GDP “an increasingly poor measure of prosperity”.

Can we do without GDP? Does the acceptance of the constraints of GDP mean that a real competitor has risen to the stage? Did we get anywhere in those ten years?

After three years of researching, I fear that my answers: no, we cannot yet do without . No, there is no real competitor. And no, maybe we haven’t made as much progress as we like to think. In the remainder of this post, I explain why.

Can we do without GDP?

Ever since its creation in the 1930s, GDP provides important information about national accounts and the size of the economy. It simply measures all production that has been created in a certain territory in a year. These data are important to inform decisions on investment, government spending, and taxation. But all too often, GDP becomes a proxy for progress or prosperity. As a tool, it only measures part of productive economy: GDP falls when a man marries his maid. Indeed, if they don’t increase the economy, GDP discounts social and environmentally desirable activities, such as household work.

Furthermore, GDP is an artificial number. Figures are routinely revised, often upwards and by large margins. After a new method is used in Ireland, GDP growth is not an already significant 7.6% over 2015, but a whopping 26% as a result of some accounting tricks. Imagine the consequences: in terms GDP per capita, Irish are suddenly a lot richer, and the budget deficit shrinks by the stroke of a pen!

Despite all these limitations, GDP is probably a bit like democracy. In Churchill’s words, democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others. We still need GDP as a tool to measure economic activity, to make sense of poverty, and to determine how much tax we need to pay to run our common society. It might still be the best we can do?

Is there any competition?

Or can we? In this blog, I’ve covered many alternative indicators, from GNH to the OECD Better Life Index to the SPI, but also the UN’s Humanitarian Development Index and even the Happy Planet Index. In my view, these are good as part of driving the narrative for a broader sense of well-being and progress. Tools like the OECD Better Life Index, GNH and the SPI can be helpful in spotting where governments need to focus resources to increase quality of life.

But they aren’t appropriate for all economic purposes. All indicators have a stronger element of arbitrary and political choices. As such, they’re too political to be used in a more economic context. Countries simply would refuse to determine financial contributions to the United Nations based on performance in the HDI, or EU regional funds based on a regional SPI score. GDP too often is seen as the more ‘objective’ metric, and even though it is not objective or stable, it is doing better than alternatives. Intriguingly, GDP is also strongly correlated with performance like HDI and SPI, even around 80% for the latter index. Although the SPI is making advances in feeding into policy, altogether none of the indices is truly challenging the position of GDP as things stand in 2016. And I don’t think it will be very different in 2018, 2020, or 2025 for that matter.

Did we make so much progress?

Then, how much progress did we make in several decades of an academic debate, and overall ten years of statistical revolution? A lot has happened. Our insights in quality of life and happiness is a deeper than at any moment in history. OECD statistical offices are now routinely gathering data on subjective wellbeing, and there is a vibrant research agenda in positive psychology and related fields. Academics and practicioners, myself included, happily travel to Bhutan to learn about GNH.

But what was generated out of this debate? Are we paying more attention to quality of life after the financial crisis? A single indicator truly competing with GDP has not been born. UN and EU authorities, as well as national governments and parliaments, have underlined the importance of alternative ways of measuring progress. But the reign of GDP has never been in danger. My feeling is that GDP is simply too important, and the alternatives too complex. I fear that we’re not ready for this revolution yet.

Time for a sabbatical

Three years on the road, my doubts on the alternatives to GDP are back. I see the beyond GDP agenda as a powerful discussion, but one that has not generated a strong enough alternative to truly challenge GDP.

On a personal level, this means that a reflection on my work is needed. Do I need to focus on something else? Do I need to work harder, or differently, for a state of happiness? Did I fail myself?

For the moment, I’ll take a break from this blog. I’ll reflect on other steps. I deserve to take some time off for a sabbatical to read more and generate other ideas. But I am sure I’ll be back with a new programme.

Because a life, enjoyably wasted in the pursuit of happiness, is a life worth wasting. Farewell!