I usually have New Year resolutions. Sometimes only one for the year, sometimes a bit too many. This year I have about five, and if there’s one that I really aspire to make, it is this one: I would like to read a book about happiness every month.

I built up a nice little collection of happiness books, so why not motivate myself to read a bit more this year. And – of course – find an excuse to buy a few extra books…

In January I read Flourish by prof Martin Seligman. I have spoken about prof Seligman, the role he played in positive psychology and the PERMA model of happiness and well-being already before. I however never read his book.

Happiness is out. Wellbeing and flourishing are in.

Flourish came out in 2011, and Seligman wrote it partially to correct his understanding of happiness in an earlier book, Authentic Happiness (2002). Over time, Seligman’s – and positive psychology’s – understanding of what happiness and wellbeing are evolved. Gradually, the distinction between happiness and wellbeing became more clear. Happiness relates to a brief, quickly passing moment, and is quite of a buzzword. It is a term easily understood by people, but when you look under the surface, it can have many meanings. Indeed, happiness is often used as a proxy for well-being or quality of life (in his book, Seligman also uses flourishing). Well-being is a more complex and generic phenomenon, describing everything what is important to a living good life.

In 2002 Seligman thought happiness manifested itself in three aspects: positive emotions, engagement, and meaning. In 2011, he argued that well-being or flourishing – a more stable and more permanent notion – should be the focus of positive psychology. He also added two ‘missing’ dimensions of flourishing: positive relationships, and accomplishment. The PERMA model was born.

The mission of positive psychology

The fundament now laid, most of the book is about fulfilling the mission of positive psychology: increasing flourishing. The chapters focus on what type of positive psychology interventions work. This can be compared to what standard psychology started to do when it was invented: find out, through academic research, what type of interventions can treat personality disorders and depression.

An example of a positive psychology ‘intervention’ is what Seligman calls the ‘gratitude visit’: think about someone in your life that did something for you for which you couldn’t thank them enough. Found the person? Now write down, in some detail, what the person did for you and what it meant to you. Then announce you want to visit the person, but don’t tell them why. When you visit the person, read out your gratitude letter aloud. I am sure that if you try it out, it will be a very powerful moment.

Seligman and colleagues then expanded these interventions in different areas. They built a positive psychotherapy programme to treat people with depression. They developed a positive education programme to reshape curricula in some pioneering schools. And they worked with the US Army to train soldiers on resilience.

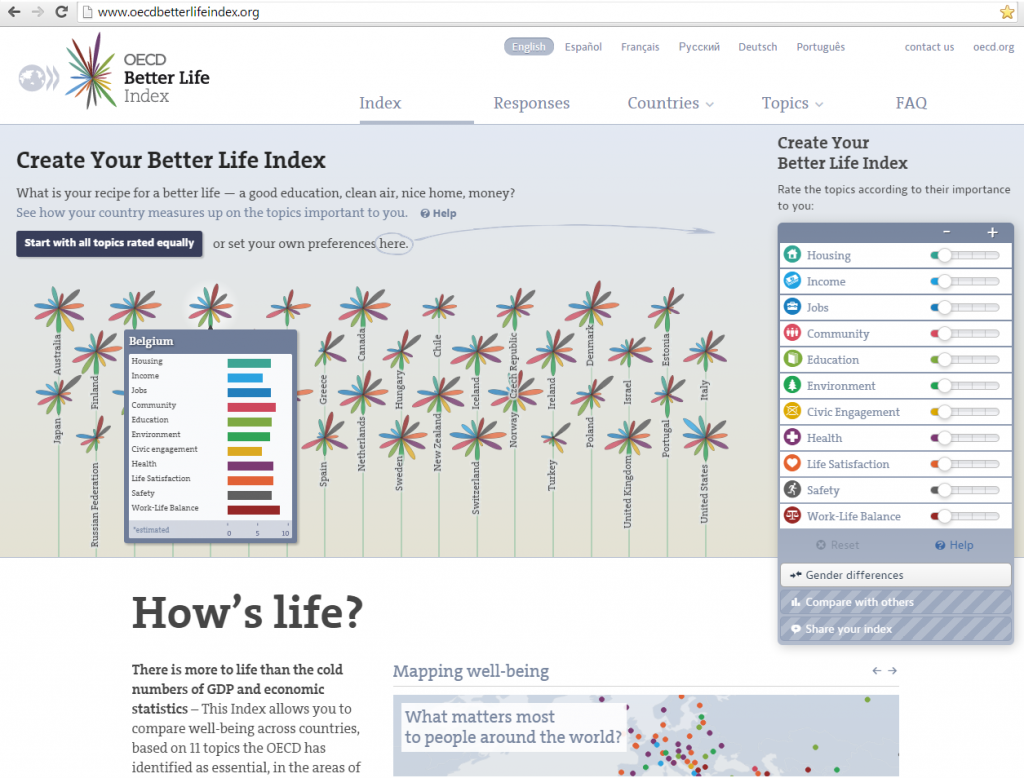

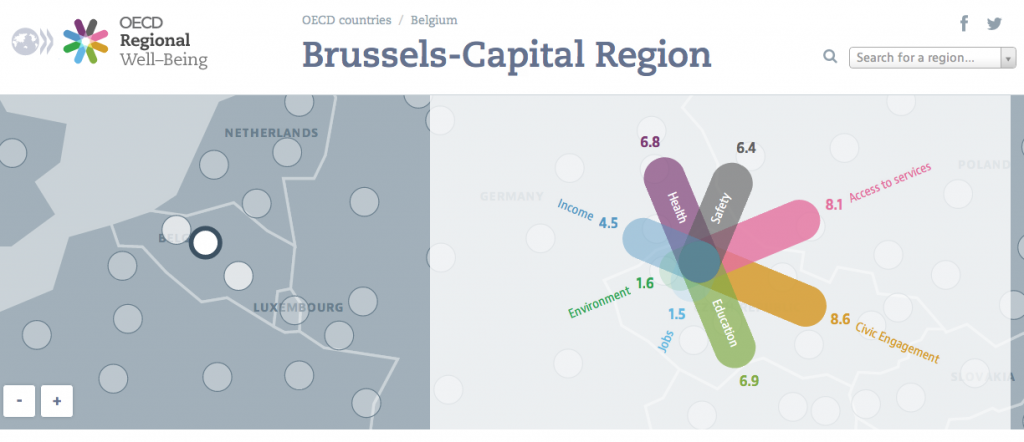

The book then even stretches on to other areas, such as the economy and happiness – it was precisely the debate on alternative ways to measure progress than GDP that brought me into happiness blogging seven years ago.

What are your signature strengths?

One of the most interesting areas, though, is the work of Seligman and co on strengths. They defined what key call ‘signature strengths’. While acknowledging we all need to work on our weaknesses, they argued it’s just as important to build on our strengths when we define our ambitions and plans for personal development. The book contains a questionnaire, which can also be found on the website of the VIA Character Institute, that helps you to identify your personal strengths out of a set of 24. I did the test myself, and for me these strengths are honesty, gratitude, and curiosity. It’s a nice narrative to think that these traits define me.

- Honesty is about authenticity, and being true to yourself. For instance, this helps to share your opinion when someone asks for it, or to name – and then improve – a bad habit.

- Gratitude means being grateful for the good in your life, and being able to express that gratitude. This can help in maintaining relationships with others (people like to hear ‘thanks’), but also to accept life events outside your control as they are.

- The strength Curiosity concerns an interest in new topics and experiences. I believe it’s a factor in personal growth, as it motivates to increase or go out of our comfort zone.

Curious what your strengths are? Read more and do the test here.